Earlier this month, Google Maps turned 20. That’s two decades of being able to chart a course across town or across continents in seconds, two decades of calculating your arrival time on your means transportation, and whether there are traffic jams or volcanic eruptions in the vicinity that might impede your progress. Two decades of scanning a destination on Street View, so you know what to look for before you arrive. Two decades in which it has become almost impossible to get lost.

When you hold up those 20 years against the roughly 2600 since maps were invented (we’ll set aside the brief Mapquest interregnum, where—believe it or not, kids—directions were generated digitally but still had to be printed out on actual paper), it’s hard not to argue that Google Maps has made the business of moving through the world much, much easier.

But that transformation hasn’t been without its costs, and articulating them doesn’t even require me to start ranting about our voluntary submission to round-the-clock surveillance. There are some more basic losses: Our navigational skills have atrophied. Same for our powers of observation; keeping your eyes fixed on a blue dot as it proceeds along a two-dimensional blue line means you’re not paying attention to your three-dimensional surroundings. And when you think about it, there’s something not a little narcissistic about the whole endeavor. That blue dot, after all, represents us, and by choosing to follow it as we move through space, we are fixating on ourselves rather than the world around us and its other inhabitants.

So I thought this was a good moment to explain a bit about how I navigate on my unplugged trips, and offer a little advice for going blue dot-less yourself.

Find a map

To be fair, you do not technically need one. After all, if you don’t have a list of addresses you must check out, your need for something that tells you how to get to those addresses is drastically reduced. But maps tell you a lot more than how to get from point A to point B. I like using them to figure out a city has developed, deduce what might be the more interesting spots, and to position myself accordingly.

So step one is to get my hands on one, and I have become acutely attuned to map-acquisition opportunities. Tourist offices will give you one for free, and there are often offices at the airport or train station (though these are often empty or have been replaced, grr, by a discreet notice telling you to scan the QR code below). Hotels will almost always have a glossy one to give you that highlights the tourist attractions. These may, on occasion, be ones that they themselves have just printed out for you from Google Maps, but they still count because you are not the one doing the printing.

Otherwise, stay alert for those You Are Here signs that some cities (thank you, Glasgow) pepper around, or descend into the metro station, where there is almost always a neighborhood map on the wall. You can, of course, spend money and buy one at a bookstore or kiosk, though these tend to be folded in a complicated origami that proves unwieldy once undone and almost impossible to recreate.

Orient yourself

Some general guidelines can help you make sense of your average European town or city’s layout. There is usually a central train station, and it is called that for a reason, which is why, even when I’ve flown into a place, I generally head there first. The oldest parts of the city, which are often the ones most appealing to visitors, are usually in walking distance from that station, but not right outside the door; look for the tallest church steeple you can see and head toward that. You’ll know you’ve reached the right place when the streets get all narrow and tangled (Broad boulevards and grid layouts come later in history, as the population grows and governments start wanting to make it easier for the military to march in and crush those pesky urban uprisings).

Intuition can help too. If there’s a major body of water in the vicinity—a river or an ocean—it’s a good bet the historic parts will border it; I found the center of Karlovy Vary just by following the river from the shopping mall where the bus dropped me off. But if the city or town is inland, finding the historic center often means walking uphill: those vantage points matter. And should your map mark a city hall or cathedral, you can be pretty certain that they’ll be smack dab in the middle of everything, including each other’s vicinity.

There are, of course, exceptions, and times where intuition will definitely fail you. I was permanently confused the entire time I was in Bologna because although the train station is to the north of the city, it feels like it is below it, which I associate with being south, and if I had tried to find the center of Biarritz from its train station, I would likely still be there.

Think of a city as a jigsaw puzzle solved by walking

I usually start by doing a light reconnaissance of my immediate surroundings, wandering aimlessly in any direction that looks interesting just to get an initial feel for a place, and then trying to relate those wanderings back to the map, in the hopes of figuring out how what I’ve seen fits into the broader landscape of the city.

After that, I use my map to choose either an interesting looking far-off point, in which case I try to head toward it in as straight a line as I can muster– or a district, in which case I just kind of meander and try to cover as much of it as I can. Either way, I’m trying to stay as observant as possible as I walk, paying attention to statues of people I’ve never heard of or the funny signs outside a hair salon so that, should I come across them on a subsequent ramble, I’ll recall that I’ve passed this way before, albeit from a different direction. One of the great pleasures of this kind of traveling are those moments when one corner of the jigsaw puzzle that you’ve been working on for hours locks into another, and you realize that the church that from a distance seemed so imposingly isolated is actually right around the corner from the drag bar where you grabbed a drink on your first night.

Make Peace with Getting Lost

Like I said, not having places you need to find dramatically reduces the risk of getting lost. But you’re probably not going to eradicate that risk altogether: there will still be hotel rooms to find your way back to, and train stations you need to locate in order to depart, and markets across town where you absolutely must go eat an eel sandwich at 5am on a Sunday. In these situations, I find it helpful to embrace the likelihood that I will get lost.

I’ve now gotten lost trying to find my hotel at 1am in Hamburg after Easter mass, and trying to find my way back from a coastal jaunt in Zadar. I’ve gotten lost looking for both of the osterias that two elderly men in Bologna each declared the best. And I have gotten profoundly and repeatedly lost along an English hill down which people ritually chase a rolling cheese.

Getting lost isn’t so bad. It forces you to relinquish that fragile illusion we all cling to called being in control; it makes you vulnerable and opens you up to the unexpected. And if nothing else, there’s almost always a half-way decent story in it.

Talk to people

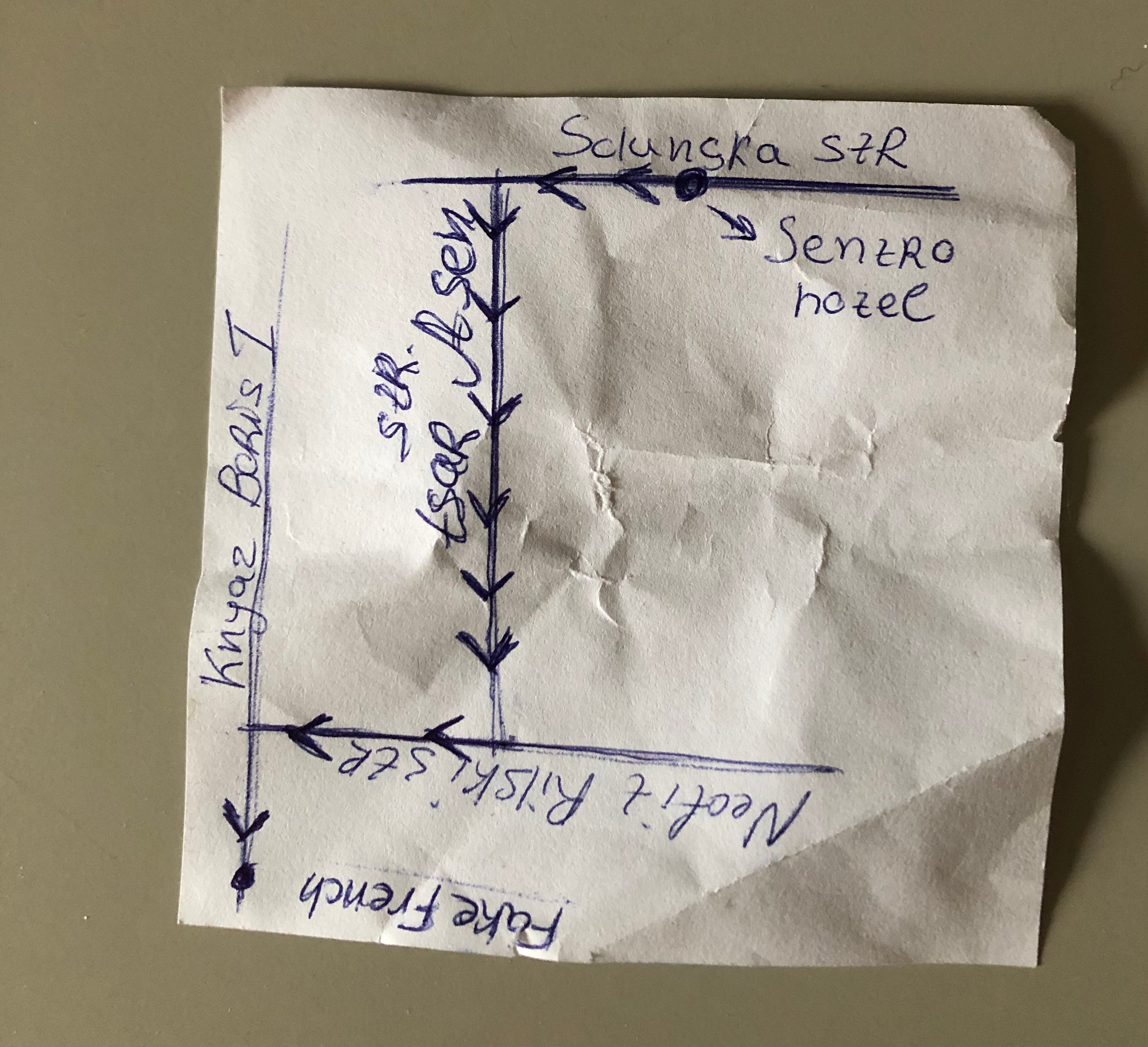

Usually, the fastest way out of getting lost is to ask an actual person for directions. When I started taking these trips, I realized that I had become so used to finding my own (re: gps-enabled) way that I had forgotten that I could talk to people and they would respond by telling me how to get to the place I was seeking. Sometimes, we would bond momentarily over this exchange, and sometimes—perhaps if a glance at me suggested to them that following instructions was not my strong suit—they might even draw me a map. Admittedly, if I was really lost—say, headed in exactly the opposite direction across an adder-covered moor from the town I intended to reach— they would sometimes laugh a little at me as they did it. But this is character building.

Keep some tricks up your sleeve

Hold on to the little paper folder that your hotel keycard comes in; it will have the hotel’s name and address printed on it. Failing that, grab the lodging’s business card, and failing that, just write the information down on a slip of paper. Keep that paper in your wallet or back pocket, ready to be pointed at helplessly should you become hopelessly lost. And remember the idea that came to me just as things were getting really grim at 1am in Hamburg: in a pinch, there are taxis.

I think that’s it for now. Have I convinced you to get in touch with your own inner navigator? Let me know in the comments.

The solution is really quite simple: Turn off Location Services (GPS), and use Google Maps.

That's what I do. I can read a map; I don't need (or want) a map that reads me.

The maps themselves are great -- better than those glossy tourist maps you're likely to find at the hotel. You can zoom in (for detail) or out (for context), and you never need to worry about wandering beyond the edge.

Oh Lisa I’m too old to get lost and be ok with it. Having said that I so love reading about your adventures and advice. They make me smile and I continue to be in awe with your courage. I live vicariously through you😀