There are people you should never ask for restaurant recommendations, at least not if you want to eat well. First among them are the staff of tourist offices, for they will inevitably send you either to highly touristed restaurants or to restaurants that are paying to be mentioned. Second among them, and for much the same reasons, are the people who work behind hotel desks.

I know: receptionists and concierges seem so obvious a choice, since they are professionally required to answer your questions, and, in the case of concierges, it’s their actual job to come up with recommendations. But if they seem an obvious choice to you, they are an obvious choice to everyone else who has ever checked into that hotel, and your average receptionist is going to have to answer the same question from all of them, so that even if a place starts out being an out of the way gem beloved by locals, it will no longer be that by the time you get around to it. You can try all your tactics—asking specifically for the places tourists don’t know about, or cleverly flipping the narrative from asking where you should go to asking where they would go— but you are not outsmarting anyone. And no, you do not have a special bond with them that will lead them to cough up that one, secret place they visit only with their most cherished friends. Sorry to break it to you. It doesn’t work.

And yet, sometimes, asking the hotel receptionist where to eat will lead you to something even better than food.

The Entry

It was only 19.30 when I landed in Biarritz, but it was dark outside, and the airport was already closed up for the night. I had chosen the destination primarily on the basis of the fact that I had to appear in a few days time at a conference in nearby San Sebastian, and this way, the conference organizers would cover my flight. But I didn’t know much about the place beyond the fact that it was on the French Basque coast, and had, I thought, kind of a glitzy reputation.

I made my way to the bus stop outside the airport where I was dismayed to learn that there was no map, just a list of lines and their stops, none of which said ‘downtown.’ I chose the one that included the ‘mairie,’ figuring that city halls are always in the center of town, and for once in my life, guessed right. I got off in an inviting area filled with shops and restaurants, and quickly found my way to a hotel where, although the front door was open, the reception desk was not–apparently whoever was in charge had gone home for the night. The same was true at the second place I tried. At the third, I couldn’t even get into the lobby.

A bit disheartened, I turned and walked in the opposite direction. This was more successful, and even though I found myself again in a darkened lobby, it was a lobby attached to a bar that was still open. When I inquired about a room, the bartender—a friendly woman with frizzy blond hair pulled into a ponytail—came out from behind the bar, flipped on the lights in the lobby, and checked me into the sole remaining room. It was very basic, with thin towels and the kind of swirling wallpaper that could give you acid flashbacks in the right circumstances, and it was only available for one night. But I was tired enough that I wasn’t going to be picky. I was also tired enough that I broke my own rule, and asked the receptionist if she had any restaurant recommendations.

She asked what I was in the mood for, and I responded by saying Basque. This earned me a modicum of respect, and she nodded approvingly at me over her glasses, before sending me to a place around the corner. “Tapas,” she said, kissing her fingertips chef-style.

A Basque would have said pintxos, and at first glance, the restaurant confirmed my worst fears: Big, packed, and with waiters running around in matching striped Breton t-shirts. I was pretty sure it was going to be a den of mediocre food and foreign languages, but previous unplugged adventures had taught me to follow the story where it takes me, so I pushed open the door. I fought my way through the scrum of patrons to an elegant woman in a cream-colored jacket and espadrilles who looked to be in charge of the place.

I expected her to be harried and none too happy to fit in a single diner on what was clearly a slammed Friday night. But she couldn’t have been friendlier, and she quickly found me a seat at the bar, calling over the bartender to make sure I was taken care of. I ordered a glass of txacoli and some moules frites, and took in the scene, which was definitely a scene. Every table in a long suite of rooms painted with murals of the Basque seaside was full, and the bonhomie was as thick as the garlic and pimentón that seasoned the heap of (delicious) mussels I ordered. Scads of waiters in their matching shirts hustled around, and seemed to be genuinely happy doing it. In fact, they, along with the elegant woman and what looked to be her two sons, greeted almost everyone who walked in the door with a smile and, as often as not, a hug. Surely not all these people were regulars?

A man in his twenties seated next to me was drinking something colored an extraterrestial shade of green. When I asked what it was, he told me it was called a Jet 27 (I would later find out it was a ‘Get 27’ but that’s French for you) and insisted I try it. He was luckily unoffended by my verdict that it tasted like toothpaste. We chatted a little: he and his girlfriend were in town for a weekend away from their home in Paris that they were spending at a friend’s vacation house. They came here every time they came to Biarritz.

A Terrible Museum, A Well-Named Dog, a Raison d’Etre

The next morning I set out to find another hotel (difficult, but not impossible) and to explore the town. For a resort, everything seemed unusually cool and appealing; chic, even. The boutiques weren’t full of tourist tat, but things I actually wanted to buy— stylish clothing, striking graphic designs, vinyl records—and even the shops clearly aimed at tourists offered well-made striped tea towels and alluringly-scented beeswax candles. There was a vintage shop stocked with Dior and other French designers whose fashionable owner had named it Harold and Maude after her (and my!) favorite movie and where her Pomeranian, also named Maude (Harold had died) kept a vigilant if fuzzy guard. There was an Art Deco casino, and a lively market packed with people carefully selecting the weekend’s cheeses at one end and slurping back oysters at the other.

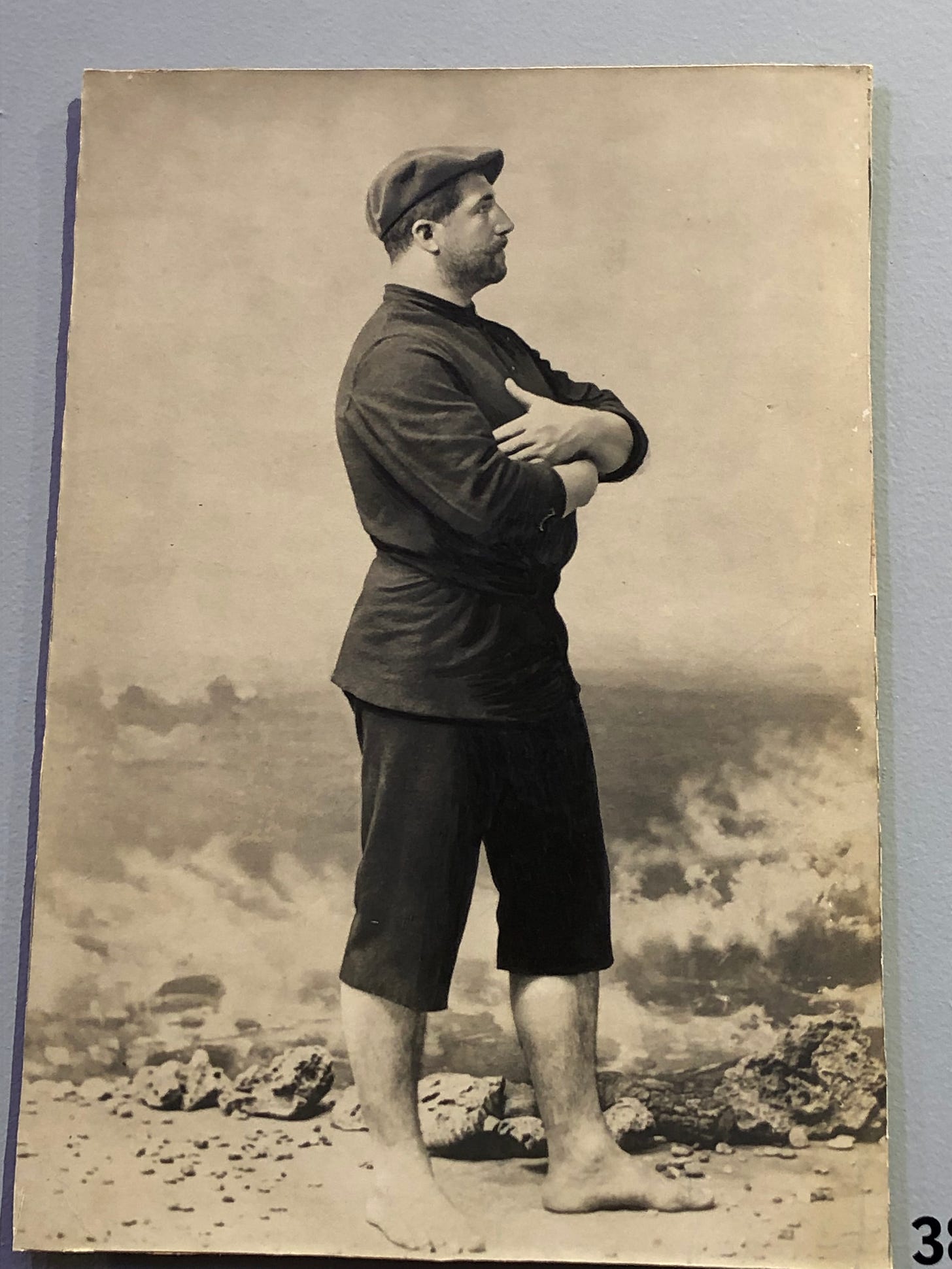

Admittedly, the local history museum looked like it had been put together by a class of 6th graders. Affixed to the walls of a former church that hadn’t even been properly emptied (a few old saints teetered in a corner next where bare tables had been haphazardly stored ), the eclectic handful of artifacts and reproduced photos was hardly worth the 8 euros I paid to see it. It did teach me, however, that the city owed its conversion from tiny whaling village to posh beach resort to a 19th-century vogue for swimming in the sea (previously, ocean bathing had been reserved as a treatment for the mentally ill). So much so that when Victor Hugo visited in the 1840s, he was smitten by the dramatic coastline and rough nature, but was also already complaining about the tourists. “My only fear,” he wrote, “ is Biarritz becoming fashionable. When this happens, the wild village, rural and still honest, will be money-hungry. Biarritz will put poplars in the hills, railings in the dunes, kiosks in the rocks, seats in the caves, and trousers on the tourists."

Too late, Vic. When Empress Eugenie began summering there a few years later , Biarritz’s conversion to luxury resort was complete. The wealthy built enormous homes in the hills above the shore, shops from London and Paris opened, and royalty and aristocrats began employing the services of the guides-baigneurs, back when life guards did not just sit on the beach flirting with girls, but actually took swimmers out into the water and splashed around with them.

The remains of that culture are still vividly evident in the Art Deco casino and the ornate villas with their Basque architectural touches that I passed on a walk up to the lighthouse, and again, (after a picnic lunch of that fig and walnut bread and some fresh goat cheese rimmed with local piment d’espelette), on the way back down, along the grand seaside promenade and past the luxury hotel that had once been Eugenie’s palace.

The views were frankly spectacular, with the blue of the sea made sharper by the dark gray rock formations that dotted it. It was a sunny October day, and there were plenty of people in the water, but it was only when I rounded the bend, after passing through the adorable fishermen’s port, that I ran into Biarritz’s true raison d’etre in force, the surfers.

What If The Beach Boys Spoke French?

This was something else I remembered from the museum: that although Biarritz’s fortunes as a seaside resort had waned in the lead up to and aftermath of the second world war, they were revived again in the 1950s thanks to surfing. The story involves an American screenwriter who was in town—along with Hemingway himself—to shoot some scenes for the movie version of The Sun Also Rises. Good California boy that he was, he had his surfboard sent over, and before long, he had introduced a handful of locals to the sport.

Seventy years later, the effects of that introduction were on clear display at the Côte de Basques beach, where the water positively rippled with surfers at all levels of ability and experience, and tents from which nearly a dozen “schools” plied their lessons from the shore. I stopped to talk with the owner of one, Thomas Gauffret, who told me he was the oldest surf instructor in Biarritz. Certified in 1987, he opened Lagoondy Surf School eight years later (the name was an homage both to the Basque word for ‘friend’ and a bay in Sumatra famous for its waves). Fifty-seven years old, he still surfed every day. “People come here because it’s mythic,” Thomas said. “It’s like going to Paris to see the Eiffel Tower. You come to Biarritz to surf.”

For much of his career, Thomas spent winters in Australia, but climate change was making it so that you could surf year round in Biarritz. “At Christmas, the water is 18 degrees,” he said. “We actually have more people coming to surf in December than going skiing in the Pyrenees because the mountains don’t have snow in December anymore.”

I asked him about other ways in which surfing has changed in Biarritz, and got a quick lesson in equipment upgrade. But more interesting to me were the cultural changes. For a while, different groups of surfers controlled different beaches, and there was quite a bit of rivalry and territorial conflict between them. Some of that was jingoistic– the French vs. the Americans and Australians who were arriving with their longboards and making Biarritz their own—and some of it was cultural. The French surfers on the Grand Plage, who called themselves the Biarritz Surf Gang, were partiers and punks who occasionally peed on competition judges and rebelled against rules of any kind, especially when they came from golden-haired foreigners attempting to ‘professionalize’ their sport.

At some point it all calmed down, and surfing became more about athleticism and wellness than about rebelling against the establishment. “Awhile ago, we organized a rugby match between the different beaches,” Thomas recalls. “And after that, there was no more tension.”

Surfing has only grown more popular since then; the number of schools offering lessons has doubled in the past five years. But when I asked Thomas if there were specific neighborhoods where surfers hung out, or bars that they frequented, he demurred. Biarritz is just one big village, he said.

As I walked through town, I could kind of see what he meant. There were parts that were more laid back, parts that felt more clearly upscale, and surf boards drying on the balconies of apartments everywhere. That night, at dinner, I talked to a waiter from Canada who had come to surf and never left; he told me that even at the height of summer, the beaches never felt too crowded, the restaurants never too full. “Maybe the locals hate having their beaches overrun,” he said. “But it never feels too bad.”

I couldn’t find a local who did hate it though. Admittedly, something like 95% of the population makes a living directly or indirectly from tourism. But I don’t think it was just the money, and I don’t think that it was just its history either. Biarritz may have been built for tourism, but it had, either by design or luck, chosen forms of tourism that seemed charming rather than tacky; respectful rather than obnoxious; and constructive rather than destructive.

Early the next morning I went for a walk, then ended up in the old part of town at an outdoor café just up the hill from the Plage de Port Vieux. As I sat there drinking my coffee, a surfer still in his wetsuit trudged uphill with his board. A middle-aged bather, sarong tied around her suit, followed a few minutes later, then another surfer, sand clinging to his bare heels, then a spear fisherman, and finally, just before I left, another surfer, this one on a scooter, wet hair dripping from beneath his beanie. Each one saluted the shop owner setting out racks of shoes across from my café in a way that suggested they knew him.

It made me think about the restaurant my first night, the one the hotel receptionist had sent me to, where the great majority of the many guests walked through the doors to kisses and hugs from the staff. Before I left, I had asked to speak with the owner, the woman in the cream jacket, and she had passed me along to her son, César, whose English was better, and who was now running the daily operations in what turned out to be Biarritz’s oldest restaurant. I asked how he knew so many of the guests—were they regulars? He told me that they were regulars and tourists, both at once. They were people who came down from Paris or Bordeaux once or twice a year, and whose families had, in many cases, been doing the same for decades.

I thought about them, and about the surfers who came from all over for the waves and the myth. The ones who joined the subculture that coursed beneath Biarritz like a riptide, and who contributed with their own ethos to the city’s relaxed, welcoming air. There was a difference, I thought, between coming to a place to consume it, and coming to join it.

The Addresses

Below, paid subscribers will find a list of the places where I ate, drank, and stayed in Biarritz. But, a gentle reminder: wouldn’t it be more fun to find your own?

Hotels

Hôtel Cosmopolitain: 1, Gambetta Street. Basic, pension-style rooms, with tiny, functional bathrooms, but smack in the center of town, clean and decorated with some seriously funky wallpaper hung with reproductions of vintage French travel posters. Breakfast better than it needs to be. 130 euros

Hotel Maitagaria, 34 Avenue Carnot. A small, family-run hotel with simple but airy rooms, a cozy atmosphere, and a scent that immediately threw me back to my first trip to Spain. 120 euros

Restaurants, bars, cafés, etc

Le Bar Jean: 5, rue des Halles. The oldest restaurant in Biarritz was taken over by the Martínez family 11 years ago, and is a bustling, joyful place where apparently everyone goes for wine, pintxos, and a heavy dose of bonhomie. Food is uneven—the mussels I had were tender, sweet, and utterly addictive; the fries that came with them bland and disappointing. But the experience is so convivial that you should go regardless. Also, they bring a DJ in on weekend nights, and the whole thing, or so I’m told, occasionally turns into a dance party

Coin de Table: 16, avenue de Verdun. They call themselves an ‘iconoclast bakery’ and with good reason: these aren’t your ordinary baguettes and pain au chocolat. Unusual and astonishingly delicious breads, like the one I tried with figs, apricots, and walnuts are made with heritage grains, and the flavorful, springy brioche are a work of art

Le Royalty: 11, place Georges Clemenceau. Can’t attest to the food at this bistro/café, but I had an excellent St Germain spritz, and got to gossip with the waiter about the owner, who, like many restaurant owners in this town, is a former rugby player. Apparently, it’s a thing in Biarritz.

Chéri Bibi: 50, rue d’Espagne. A confession: this place wasn’t completely unknown to me. In the weeks before my trip, every time I told someone in Copenhagen that I was going to Biarritz, they asked if I was going to eat at Chéri Bibi. I decided I would go only if I came across it spontaneously in my walks, and on my second day there, as I left the Côte des Basques beach and wandered through the working-class neighborhood nearby, I did. The serious hipster vibe suggests the owners did some time in Copenhagen? But the food, including an astonishingly good pumpkin dish and some very fat anchovies, was excellent and the all-natural wine list was solid.

I think this is your best Unplugged Traveler yet. It feels more centered and organic than some of the others.

Your vivid portrayal of Biarritz captures the city's unique charm and coastal allure. The blend of cultural insights and personal anecdotes paints a compelling picture of this seaside destination. Thank you for sharing such an engaging narrative.