Karlovy Vary (Also known as Karlsbad. And Carlsbad)

Peat baths, holographic Kafkas, and a Europe-sized dose of nostalgia

So far, the best thing I’ve discovered about traveling without the internet is that it can make almost anything feel like a discovery.

Before I arrived, I knew Karlovy Vary was an old spa town, one of those cosseted destinations, far from the pressure and pollution of urban life, where European society once retreated to heal itself with warm soaks, refreshing walks, and the occasional illicit romance. As someone who read The Magic Mountain as an aspirational travel guide (what bliss to spend your days wrapped in fur blankets on a balcony overlooking the Alps, even if it did require a tiny tuberculosis diagnosis), I have spent a lot of time imagining what the culture that sprang up around Europe’s spas and sanatoria was like. But my imagination hadn’t quite prepared me for Karlovy Vary: the whimsical architecture, the strange treatments involving gas and peat; the ornate colonnades built for rain-free strolling, the sheer Wes Anderson-ness of it all. And I certainly wasn’t prepared to feel nostalgia for a place I had never before been.

I arrived by bus from Prague, after a 75-minute ride seated next to a large lady with a frizzled halo of pale hair who spoke to herself in a baby voice for the entire journey into western Bohemia. I left my bag with the one-legged man overseeing both ticket sales and luggage deposit at the station, and headed into what I hoped was town, following my hunch that the river would lead to the center.

It did, and within minutes, I was in its sugarplum heart. Karlovy Vary is a confection of a place, from its candy-colored villas ornamented with Art Nouveau turrets and curlicues, to its waitresses in their frilled aprons, to the actual cake shops with windows filled with spun sugar and rolled sponges. People strolled through gardens and beneath gazebos sipping from delicate porcelain cups. One colonnade, its intricate fretwork painted white, looked like a Carême meringue.

My first few attempts to secure a hotel room were unsuccessful: although each of the first three I entered was invitingly ornate on the outside, the interiors were either oligarch tacky or Soviet grim. But I was spared the awkwardness of rejecting them because, though it was past 10am, the reception desk in each was utterly unstaffed. Finally, I came to the Hotel Romance, at which point I realized my previous failures all made sense. Because if you’re going to visit what is essentially one big Wes Anderson set, a stay at the Hotel Romance seems part of the deal.

From the narrow reception cubicle inside, Blanka welcomed me cheerfully. Dressed in a crisp white blouse and a sensible navy skirt, she offered me a single room for the suspiciously low price of 40 euros, and seemed delighted when I asked if there might be anything a bit nicer available. “Why yes,” she replied with a twinkle. “We have a beautiful room with a view of the colonnade that I think you will like very much.”

She was right: the room was faded but elegant, with gilt-framed lithographs of Venice on the walls and sashed curtains on the large casement windows, from which I could just make out the letters indicating the Hotel Romance’s former incarnation as the Hotel Pushkin.

After heading out again, I followed the river further, past shops filled with expensive looking sneakers and a beer hall named after Goethe. Soon, I came to a massive wedding cake of a hotel, stretched long against the side of the hill, its white façade and columns contrasting sharply with the deep green of the woods behind. This was the Grandhotel Pupp, whose very name felt like a catapult back to another century, and which was, in fact, an inspiration for The Grand Budapest Hotel. The chandeliers and brocade in the lobby, the dining room adorned with blossoming almond trees; the perfect little brass-lidded ice cream cart outside–it was all too much, and that was before I looked down.

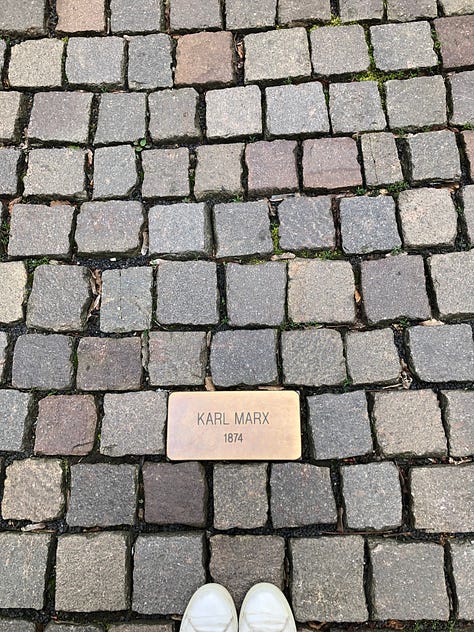

Outside, a bit of lettering on the ground caught my eye. Upon closer inspection I saw that it was a brass brick, and that it read ‘Sigmund Freud.’ I was marveling at the thought that Freud had stayed at the hotel, when I saw another: Antonin Dvorak. And another: Karl Marx. There were dozens of them, I realized, spanning the centuries, from Peter the Great to Richard Wagner to Luis Buñuel to Vaclav Havel to that greatest of cultural luminaries, John Travolta. All of them had been guests in the building, and except for the movie stars (Karlovy Vary’s film festival was once considered the second most important in Europe, after Cannes), they had come to be cured in the town’s thermal springs.

And it wasn’t just that hotel. A bust on the edge of town commemorated the spot where Goethe would take walks, just like a statue, a bit further on, does for Beethoven. Nearly every building bore a plaque designating its one-time occupants: Pavlov, Ataturk, Chopin, von Bismarck. Friedrich Schiller started The Wallenstein Trilogy while staying at the spa; Gustav Klimt designed the curtain in the town’s theater.

If I had arrived in town having done research, I probably wouldn’t have experienced that small, thrilling moment when I realized what all those bricks and plaques meant. And I almost certainly would have missed out altogether on the Imperial Baths, because I would have read about this cultural moment and concluded, honestly, how interesting can an abandoned bathhouse with a really fancy tub be?

Instead, I naively approached a very grand building not far from the Grandhotel Pupp and, finding its doors open, decided to go inside. A woman there sold me a ticket and tried to show me on the map where I could and could not go, but neither her English (poor) nor my Czech (nonexistent) were up to the task, and I headed down the corridor she pointed with no clear sense of what I was getting myself into.

I figured it out pretty quickly. Though the entryway–all plush red carpet and marbled staircases–was ridiculously luxurious, heavy doors opened to a bare, clinical corridor, lined with large windows on one side, and identical doors on the other. I was alone, and a definite Alice-in-Wonderland feeling came over me as I entered the first. It was empty except for an animated cartoon playing on one wall: a video installation that explained what had once gone on in these rooms.

Inaugurated in 1895 and named for the Emperior Franz Josef who visited in 1904, the Imperial Baths were the largest and grandest of the many spa houses in what was then called Karlsbad (Or Carlsbad. Spelling seems a bit fluid). It included a concert hall, richly-panelled waiting rooms, and a gymnasium complete with cutting-edge fitness machines. But the heart of the spa were the baths themselves, these small chambers with tubs where the patient–-suffering from gastrointestinal ills or sluggish metabolism or just general malaise–-would soak in water from one of the many local springs best suited for their ailment. One of its most sought-after treatments was the peat bath, where the water was mixed with the mulch from the surrounding woods, which was (is?) also believed to have curative properties.

Admittedly., taking a bath in a tub full of dirt and rotting leaves does not sound all that appealing, but in comparison to being injected with the gas emitted from those rotting leaves (another signature treatment, and purportedly good for joint pain), it sounded downright indulgent. When I learned of the building’s ingenious hydraulic system, which brought a full tub of clean water up from the basement while the dirty one sank into the floor and was whisked away on tracks, I was fully smitten. And that was before I opened the door onto a chamber where a life-sized hologram of Franz Kafka soaked moodily, his boney knees emerging Iike deliquescent icebergs from the peat-blackened water, his fingers drumming restlessly on the side of a tub.

For all the spontaneous discoveries, however, there were also downsides to coming unprepared. By now, of course, I wanted a peat bath of my own. But when I inquired at the tourist office on how I might go about getting one, I was gently informed that I had basically done it all wrong. You didn’t just show up in Karlovy Vary and ask someone to draw you a bath. Treatments here were serious business, complete with blood tests and a doctor’s supervision, not something you could order up like a pizza. Most spa-goers signed on for at least a two-week course, and most of the spas were in hotels, available only to their own guests. Had I inquired at mine?

The Hotel Romance might have an irresistible name, stately rooms, and the crisp-bloused Blanka at reception, but it did not, alas, have its own spa. Once, guests used the public one in front of the hotel, but it had closed during Covid, never to re-open. There were a couple of other public spas, but they did not offer baths of any sort on the weekend. If I just wanted a soak in the mineral waters, however, I could try the Thermal Hotel.

I had noticed the Thermal on my way into town-–it was impossible not to. A Brutalist highrise plunged like a concrete dagger into the delicate heart of Karlovy Vary, it was festooned with billboard-sized banners promising spectacular views and 38º water. I was astonished the townspeople hadn’t risen up with pitchforks for this crime against its aesthetic integrity, but I also didn’t want to leave town without at least one soak.

In the meantime though, I picked up a map of what were essentially public faucets. Taking the cure in Karlovy Vary involves not just soaking in its many warm springs, but also drinking from them, and there are about 20 spigots scattered throughout the town, some housed beneath elaborate colonnades built to protect strollers from inclement weather, some little more than taps jutting out from the ground. This too proved to be serious business; the map warned that drinking from the springs also demanded a doctor’s oversight because the “chaotic intake” of mineral water could be harmful, resulting, remarkably, in both diarrhea and constipation.

I decided to take my chances. I bought a porcelain cup from a vast array at one of the kiosks set up for this purpose, and chaotically filled it at the first faucet I came to. The water was hot and tasted sulfuric in a way that seemed convincingly medicinal. I did not notice any effect on my bowels.

I did notice quite a lot of tourists. though. Some of these were Czech, and they seemed to be there for the spas. But a lot were foreign—either families drawn by the swimming pools and all-inclusive meals, or tour groups stopping to pose next to the columns as they were shuffled from one end of town to the other. Very few of the foreigners seemed to be there for the treatments, and although I would inevitably encounter one or two fellow sippers as I moved from faucet to faucet, they seemed to be like me: the semi-skeptic doing it for the experience, rather than patient hoping for a cure.

Karlovy Vary has always been a tourist town. But I found myself wondering now about it what it meant that those tourists were no longer coming to participate in spa culture, but rather to observe what remained of it. In truth, the decline began a long time ago, when the Germans who had for a while taken ownership of this part of Bohemia were expelled from it after the Second World War, and the Czechs who had suffered under Nazi rule found themselves with little appreciation for German culture. As the country was sucked into the Soviet sphere of influence, Karlovy Vary went from aristocratic retreat to a holiday destination for the workers. The Grandhotel Pupp was nationalized and renamed The Grand Moskva. The “clientele changed,” as the current website puts it with still barely-suppressed outrage, “and the luxury suites were enjoyed by communists.”

One of the first repercussions of the Velvet Revolution was for the Grandhotel Pupp to reclaim its proper name and restore those luxury suites, one assumes, to a more suitable clientele. But the world, by then, was a different place, and spa-going was no longer had the position it once did in most of Europe. In fact, the only people who could reliably be counted upon to seek out medical spas for their holidays were Russians. Once again, Karlovy Vary adopted to the new influx, and I could still see signs of their flexibility, in the shops with names like Glamour, Aristocrat, or simply Rich that sold Gucci handbags and caviar-infused cosmetics. A champagne bar advertised happy hour discounts on Cristal. The opera and theater that for decades provided entertainments in the evenings were now supplemented by performances from touring Russian comedians.

In that way Karlovy Vary made it through the pandemic. But all that changed in 2022. In response to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, the Czech Republic banned Russians from entering the country. The banishment is not absolute; plenty of Russians who were already living in Europe or who fled there at the war’s start, still find their way to the spa town. But with its core audience greatly diminished, Karlovy Vary has languished. There’s been some attempt to draw new audiences, with the Grandhotel Pupp, for example, firing its staff doctors and converting its storied medical spa to an Ayurvedic one. But by the time I arrived late this spring, it seemed like the end of something.

I tried the Thermal Hotel, and found it as dispiriting as I expected. But from its small, rooftop pool of hot springs water, I spied the Elizabeth Spa, and decided to make one last stop. Built in the early part of the 20th century, but made to look like a Baroque palace, it is one of two remaining public baths in town, and sits grandly behind a fountain at the end of the long alley of lime trees. Up close, however, I could see the white paint peeling from its façade, and the plaster crumbling. Inside, a lone attendant who seemed glad for the interruption happily agreed to answer my questions. He told me that the spa was nowhere near as busy as it had once been, and when a leak destroyed the roof in part of the building, funds were so short that instead of repairing it, the whole wing was permanently shut down. Czechs still came to the Elizabeth–the cost of treatment was covered by their national health insurance if prescribed by a doctor. But without the Russians, the attendant said gloomily, he wasn’t sure how long they could stay open.

I asked if I could have a peat treatment, but no, the baths were closed on Sundays. I could, however, get a massage.

I followed his instructions down the broad staircase, past empty clinical hallways giving off scary sanatorium-horror flick vibes, and doors marked with things like “Irigace Inhalace,” which even in a foreign language, I’d rather not think about. Eventually I found room 26, and Tereza, who looked exactly like you’d expect a Czech masseuse to look. She ushered me into a treatment room that will not be featured in the pages of Goop anytime soon, put on a recording of Leonard Cohen live in concert, and gave me what may well be the best massage of my life.

I felt lighter when I left, but also sadder. Whatever the therapeutic properties of Karlovy Vary’s mineral springs, it wasn’t hard to imagine why a couple of weeks of warm baths and long walks in the crisp mountain air might make all those European elites— jacked up on the nerve-jangling energy of industrialized cities and intellectual foment— feel better. It would have made me feel better too.

I found myself longing to experience it, and wondering if I ever would. Maybe if I came back in a month or a year, prepared this time to submit to a proper, non-chaotic course of treatment, I could get a taste of it. But I’m not sure that Karlovy Vary will be able to hold on to its essence for much longer. Already, the observers of spa culture must outnumber the participants. How long before the meaning of the place is hollowed out entirely, leaving behind only the villas and colonnades, like a cicada’s ghostly shell?

The Addresses

Below, paid subscribers will find a list of the places where I ate, drank, and stayed in Karlovy Vary. But, a gentle reminder: wouldn’t it be more fun to find your own?