The Heroes and Villains of Gdansk

Sure, you could watch the Inauguration. Or you could ponder the politicization of history

As you may remember from last time, there were many things I did not know about Gdansk before I went there, including:

It has gorgeous architecture

It has excellent doughnuts

It has Lech Walesa soup memes

There’s one more important thing to add. Gdansk, it turns out, is where World War Two started. On September 1, 1939, a German battleship pulled into the harbor of what was then the free city of Danzig and started firing on a Polish munitions depot.

Probably all of you know that. I mean, it’s a pretty big fact, so big that I’d like to think that I once knew it and it just got crowded out by, I don’t know, old Mazzy Star lyrics and the really good granola recipe that has taken up permanent residence in my head. But it wasn’t until I walked along the city’s waterfront promenade on my last morning in Gdansk, spied signs for the Museum of the Second World War, and then actually went to the museum that I learned (recalled?) this other starring role the city played in 20th century history.

The museum sits roughly between Westerplatte, where the depot was located, and the Gdansk post office, where workers fended off an initial SA siege for 15 hours. Actually, ‘sits’ isn’t the right verb, because the building looks like a jagged shard of shrapnel plunged aggressively into the skin of the earth. Above ground, a rhombus of brick and glass juts into the horizon, but the museum itself is located below. To see its tragedies and horrors and occasional glints of heroism, you must descend into the earth.

There, the exhibits are assembled in a warren of chambers arranged along two sides of a long narrow corridor topped many stories above by a line of glass—the crack where, as Leonard Cohen might put it, the light literally comes in. Which is definitely welcome, because there is nothing quite like seeing the history of that war laid out in excruciating detail on a gloomy November morning in the year of our Lord, 2024, to put one in a fretful state of mind.

The collection is massive; no less an authority than

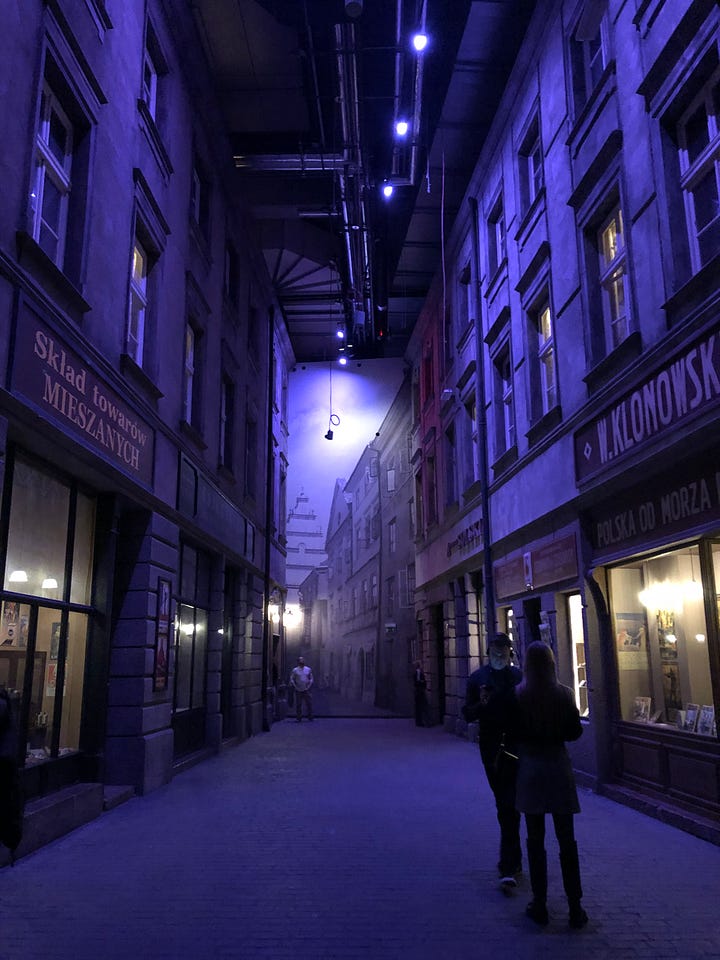

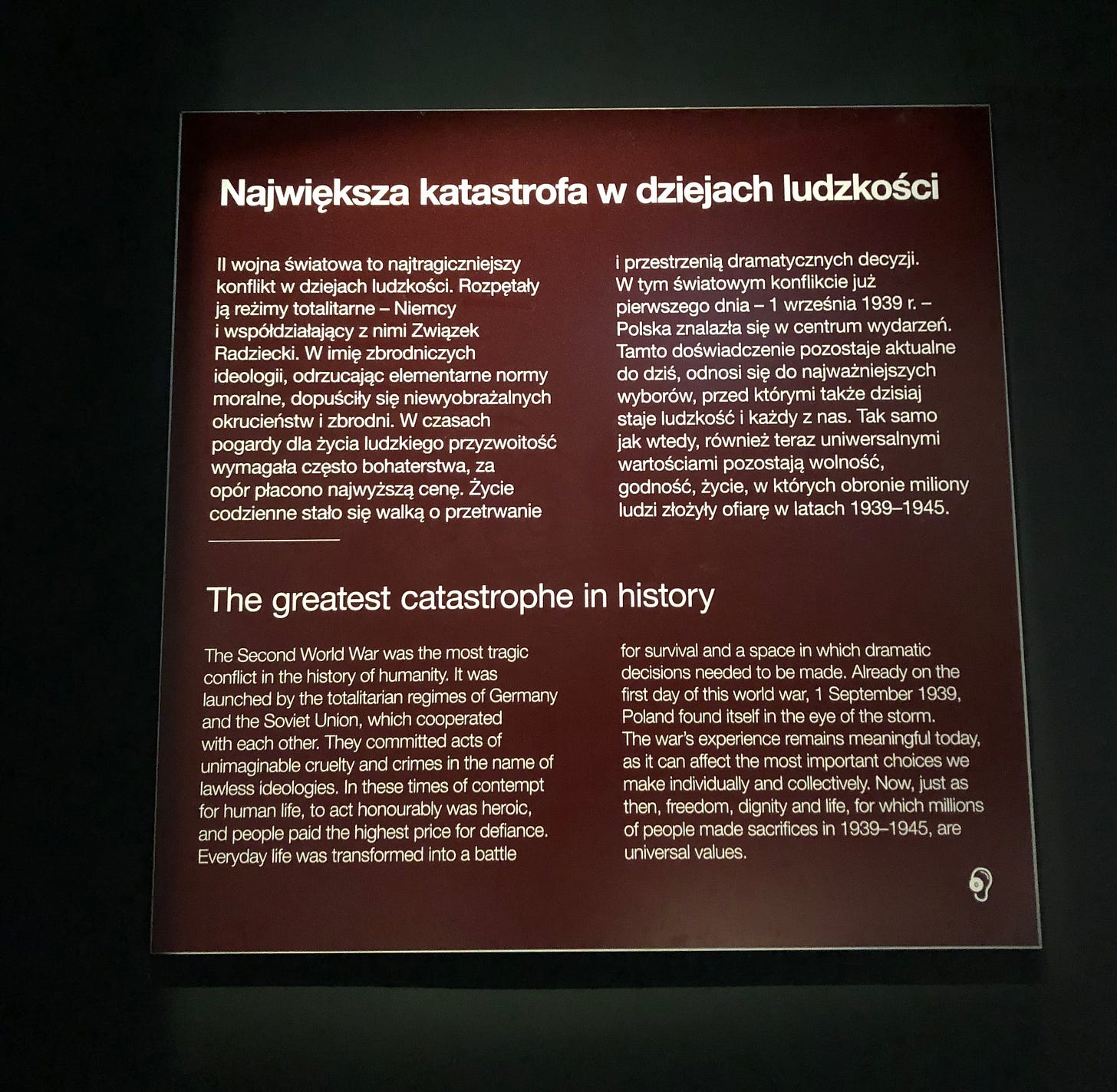

called it "perhaps the most ambitious museum devoted to World War Two in any country.” It took me nearly an hour just to get to 1939, and it was not a carefree hour, let me tell you. The first galleries, which include a remarkable life-size recreation of a Gdansk city block in the mid-1930s that you can actually stroll down, chart the rise of totalitarianism and the increasing brutalization of politics with a palpable sense of growing dread. By the time I got through the warmup–the threats and appeasements, the territorial incursions and forced resettlements, the politicization of just about everything— to the actual conflict and everything it unleashed, I didn’t need the human-sized block letters spelling out the word TERROR that guard the museum’s darkest chambers of horror to feel just that.I mean, the place is unrelenting. But it’s also fascinating, because it tells the story of the conflict from Poland’s perspective. Which is not a perspective I had considered before, and definitely not the one this American learned in school. In this telling, Germany and the Soviet Union are both the aggressors, and Poland is caught in the middle, squeezed unremittingly from both sides.

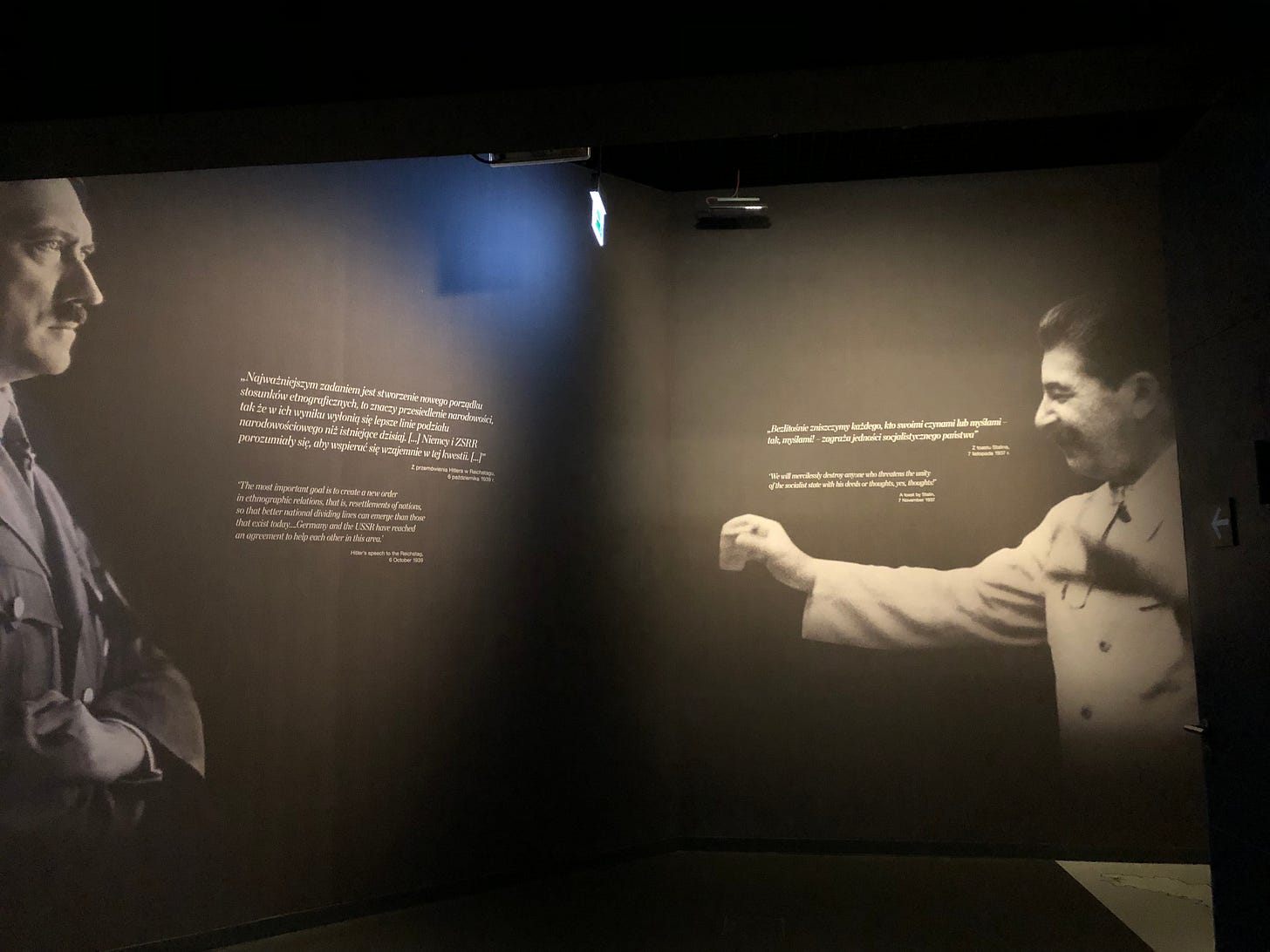

The exhibits make this equivalency visually at every turn, juxtaposing Nazi and Soviet propaganda, turning Molotov-Ribbentrop into a dramatic climax of sorts, and even using the building’s architecture to literally convey the sense of the walls closing in. But it also just comes out and tells you.

I was so struck by the guiding perspective that at one point I approached a docent who looked, if not old enough herself to have been alive during the war, at least old enough to have grown up with parents who vividly remembered it. I asked her, in English, if that was, indeed, how she understood the war. She stared at me blankly, in a way that made me really want to whip Google Translate out of my pocket. But I resisted, and soon she made one of those downward air pats that apparently mean ‘follow me,’ because the next thing I knew we were powering past bomber planes and Enigma machines as she led me on a meandering trail through the maze of galleries. I thought we must be looking for the display that would answer my question. But no, we were looking for Ludmilla.

“Can I help you?” she asked, in flawless English. By now, the original docent, who had clearly assessed and remedied the communication problem, had disappeared. Ludmilla was much younger, but I asked her my question nonetheless: did she grow up with this sense of the war, of thinking it had been started equally by both Germany and the Soviet Union? That they were equally bad and bore equal responsibility for what happened?

“Well,” Ludmilla said. “I’m from Belarus. So I grew up thinking the USSR won the war completely on its own.”

It wasn’t until she moved to Gdansk in 2018 that Ludmilla learned the Americans might have had a little something to do with it. But by then, she had also learned that, as she put it, “every country has its own story.”

Later, when I got back home, I would learn that Poland was still figuring theirs out. Soon after the museum opened in 2017, it was rocked by a huge controversy: the government that had commissioned it had lost the election to the right-wing, populist Law and Justice party, and the new government did not appreciate its predecessor’s universal approach to the subject of world war. At a time of rising nationalism and far-right marches in Warsaw calling for a “white Europe,” the Law and Justice-led government fired the museum director, replaced him with someone who shared its brand of patriotism, and re-did parts of the exhibitions to better center Poland, playing up its roles as both victim and hero in the story.

I think that must have been the version I saw. But I’m not sure because by the time I rolled up late this fall, the government had changed again, and this new coalition, led by Donald Tusk, was determined to restore the democratic institutions eroded by the previous one. Which included firing the second museum director, installing a new one who had worked on the first exhibition, and restoring the museum’s original, universalist intentions. They made that announcement five months after I got there, but these things surely take time; in any case, the collection still seemed pretty Polish-focused to me. But then again, like Ludmilla, I grew up with a different story.

After a little more than two hours in the place, I was feeling pretty wrecked. But I dragged myself to one last gallery. Off a darkened room where illuminated columns of photos–the identity cards of Polish Jews killed in the Holocaust—streamed from the ceiling, was another recreation. It was another street that, like the earlier one was true to size, so that you could stroll down it. Only now you couldn't really stroll, because the street was a blackened ruin, the buildings reduced to pocked concrete and ash, a Russian tank parked onto the rubble that had once been homes.

Eventually, that rubble that would be rebuilt into the gorgeous Gdansk that I found so enchanting. But it was hard, as I walked back into the Old Town in search of a much-needed doughnut, to forget what had come before, to forget the reality—no matter what story was told– that lay beneath the surface.

This sounds like a museum I’d be interested in visiting. It’s so important to remember how politicized history can be, depending on who’s doing the telling. We forget about the long run-up to the horrors of WW2 and the dire consequences of unchecked nationalism, xenophobia and racism at our peril. Your post has particular resonance right here and now. Thanks for sharing, Lisa.

Am trying to come up with something positive to say, and almost failing. Another excellent piece, Lisa.