Sofia

In an era when European capitals are increasingly becoming more like each other, Sofia does its own thing

Among the things that I thought might happen during my travels when I started this newsletter, sitting in an ornate theater to watch a play written by George Bernard Shaw, directed by John Malkovich, and violently protested by pro-Putin Bulgarians was not on my dance card. And yet, two days into my trip to Sofia, there we were.

There had been no tourist desk at the lonely terminal in which lowcost flights to the Bulgarian capital arrive, so I was trying to figure out how to get to the city center when I overheard a man (middle aged, lavender hoodie) asking a group of young Spaniards kitted out in expensive Nordic winter gear where they were going. I suspected that this was a hustle, and expected him to soon herd them into his ‘taxi’ for what would turn out to be an exorbitantly priced journey and a possible visit to his “uncle’s” rug shop. But friends, I’m just going to take a moment to remind you what Oscar Wilde said about cynicism, because the man—who turned out to be an architecture professor home for the weekend—kindly led the Spanish kids to the metro, taught them how to buy a ticket (the entire Sofia transport system operates with just a tap from your bank card), and gave them advice on how to get to their Airbnb. I know all of this because, of course, I stalked them.

I emerged from the metro with that dreamlike sensation of having gone to sleep in one world and woken up in another. In front of me were street signs written in Cyrillic, and a large Orthodox church, fat and domed. Behind me loomed a Soviet-era building that, in both its size and its severity, seemed designed to intimidate and, just opposite, a statue of a bosomy woman (that would be Sofia herself) on a tall pillar, jutting arms and breasts into traffic. A couple hundred meters away, a minaret soared into the graphite sky.

The architecture professor had told the Spanish boys that Vitosha Boulevard was the city’s central thoroughfare, and now, having bought a map from an underground kiosk before I exited the station, I headed toward it, dodging the melting icicles of the previous day’s winter storm. With its retro trams trundling past, and the stolid, slightly tacky clothing on display in shop windows, Sofia felt unmodern, as if I had traveled not only across physical space, but through time as well. Even Vitosha, which is the kind of banal pedestrian boulevard you find everywhere in Europe these days, felt ever so slightly out of date, the normal array of poké restaurants and H&Ms tucked in among 1930s-era block housing and convenience stores named Kinky.

The first hotel I saw didn’t look like my kind of place, but as I headed toward it, I came across another, with the words YES, WE ARE OPEN taped to a window, and a wistful-looking man loitering in the doorway. The hotel, small and vaguely stylish, had opened a month or so earlier. “We want to offer the best service in Sofia,” said the man, who turned out to be the receptionist and was no longer loitering wistfully. I checked in, dropped my bag, and headed toward what looked to be a central square.

A sign there identified a glass structure as the tourist office, but the profusion of books inside made me think I had mistakenly entered a library. “Yeah, it’s a reading room too,” came a voice from behind a desktop stack. It turned out to emanate from a strikingly pretty 20-something with multiple piercings and a more jaundiced view of her city’s charms than you might expect from your average tourism professional. She pulled out a map and began circling the capital’s attractions with a warning. “There’s not much,” she sighed. “Most people just do the communism tour.”

I said I was interested in the city’s multicultural history, and that I had thought I’d seen a mosque when I got off the metro. “Yeah,” she conceded. “We were slaves of the Ottomans for 500 years. So…” she shrugged, the implication apparently obvious enough that it didn’t bear finishing the sentence.

“What about outside the center?” I asked. “Any cool neighborhoods you like to hang out in?”

“You heard me mention communism?” she asked in a tone one might use with an especially slow toddler. “There are no cool neighborhoods.”

But I liked Sofia. Part of that was the sheer idiosyncrasy of the city: it didn’t feel like anyplace I had ever been before. The streets of the center are paved with yellow bricks first laid about 7 years after the Wizard of Oz was published but apparently owing nothing to them. A former covered market has been turned into a supermarket that could pass as a Whole Foods in its golden, pre-Amazon era. There are lovely little Orthodox churches tucked in among the apartment buildings, and a beautiful old Sephardic synagogue, its cerulean ceiling speckled with gold stars. A block away is the mosque I had seen when I first arrived, where the call for prayer draws a large enough crowd that they can’t all fit inside; the spillover lines up outside, unrolling their rugs in the bitter cold.

The former bathhouse has been turned into a not-terribly-good local history museum, but off to the side, people still fill plastic bottles with the hot, presumably curative water that spills from its taps. There is an open-air market where the babushka tradition lives on: sturdy women seemingly impervious to the frigid temperatures, selling honey, cabbage, and homemade cheese. There are some faded, beautifully ornate buildings that hint at a more elegant era. There are a lot of statues of soldiers.

And there is the Aleksander Nevsky Cathedral, astounding in its size and bulbosity. The drama of the structure intensifies once you enter, and the incense, gold, and flickering forest of candles combine with an interior whose every surface is covered with soaring paintings of saints. A handful of faithful were there to pray among the smattering of tourists, though it wasn’t always easy to tell them apart. One graceful young woman, dressed entirely in black with an embroidered shawl draped over her head, moved so mournfully through the vast sanctuary that I thought she must be a grieving widow; turns out she was scouting an optimal selfie location. But I wasn’t wrong about the large, middle-aged man who went sorrowfully from one icon to the next, touching the saint’s image, then crossing himself and murmuring a few words of prayer. Pain radiated off him, and when I left the church, he was standing on the stairs outside, looking out despairingly, as if he were uncertain of where or whether to go next. “Are you okay?” I asked. But he just shook his head, turned, and walked away.

I did find a coffee shop that wouldn’t have been out of place in Copenhagen, on a block with a bar specializing in board games and mead, and a short term apartment building for digital nomads with one of those Communism fetishes the tourism woman had mentioned. But there was no adorable Old Town, and–as far as I could tell–no gentrifying hipster neighborhoods. When I stepped into a bakery near the mead bar, and told the baker that the area looked to be up-and-coming, he didn’t seem convinced. “I don’t know,” he said, “Maybe we try?”

That vein of doubt and even self-recrimination kept surfacing during my time in Sofia. When I asked if I could enter the grand building housing the national library, the guard there made a noise that sounded suspiciously like a scoff and said, “There’s not much to see.” (To his credit, he had a point). I stumbled across an exhibition by Bulgarian photographer Garo Keshishian depicting the conscripted labor service (under Communism, it had forced mostly ethnic minorities, criminals, and dissidents to work on large scale construction projects and had continued, astonishingly, until 2000), where the tone of the accompanying texts was less outrage than embarrassed resignation. I ate dinner one night in a lively, perfectly respectable French restaurant that anywhere else would have called itself Chez Marcel or Le Petit Cochon or some other cloyingly francophiliac name. But here, as if to preventatively ward off any attempt to hold them to standards they weren’t sure they could meet, the restaurant went by the name ‘Fake French.’

Everywhere, I kept running into an acute awareness, even sensitivity, to history. Though it’s now been almost 150 years since the Bulgarian liberation, the preceding 500 years under the Ottoman yoke clearly did a number, and both events, liberation and enslavement, pop up with surprising regularity, not only in formal settings like the markers on street corners, but in casual conversation.

“At first I thought all Bulgarians were all racists,” Camilo told me. I met him when I followed a sign promising hot chocolate to the Guatemalan consulate in Bulgaria; that Camilo himself was not Guatemalan but Cuban was only one of the unlikely things about the encounter. He had arrived in Sofia two years earlier as a student (apparently, the old Socialist connections still apply when it comes to study abroad) then stayed on, even though in the beginning, he was uncomfortable with how the locals would always stare at him. “But now I think they’re just observant. They were slaves of the Turks for all that time, so I think they’re just wary of outsiders.”

The other part of Bulgarian history that seemed ever-present was the Soviet past. By then, I had already had my own encounter with Soviet nostalgia at a popular restaurant where the soup and banitsa were tasty, and the decor was all Martisa typewriters and Rekord television sets.

Now, Camilo explained to me that it wasn’t all in the past, and that Bulgarian society was divided into pro- and anti-Russian camps. “There are a lot of old people who think things were better under Soviet times, and some young people too,” he said. But they were influenced, he thought, by their distance from the past. “The way you can’t speak out… I tell them ‘you haven’t lived it in 30 years. But I lived it until I left 2 years ago.’”

And then, there was the theater.

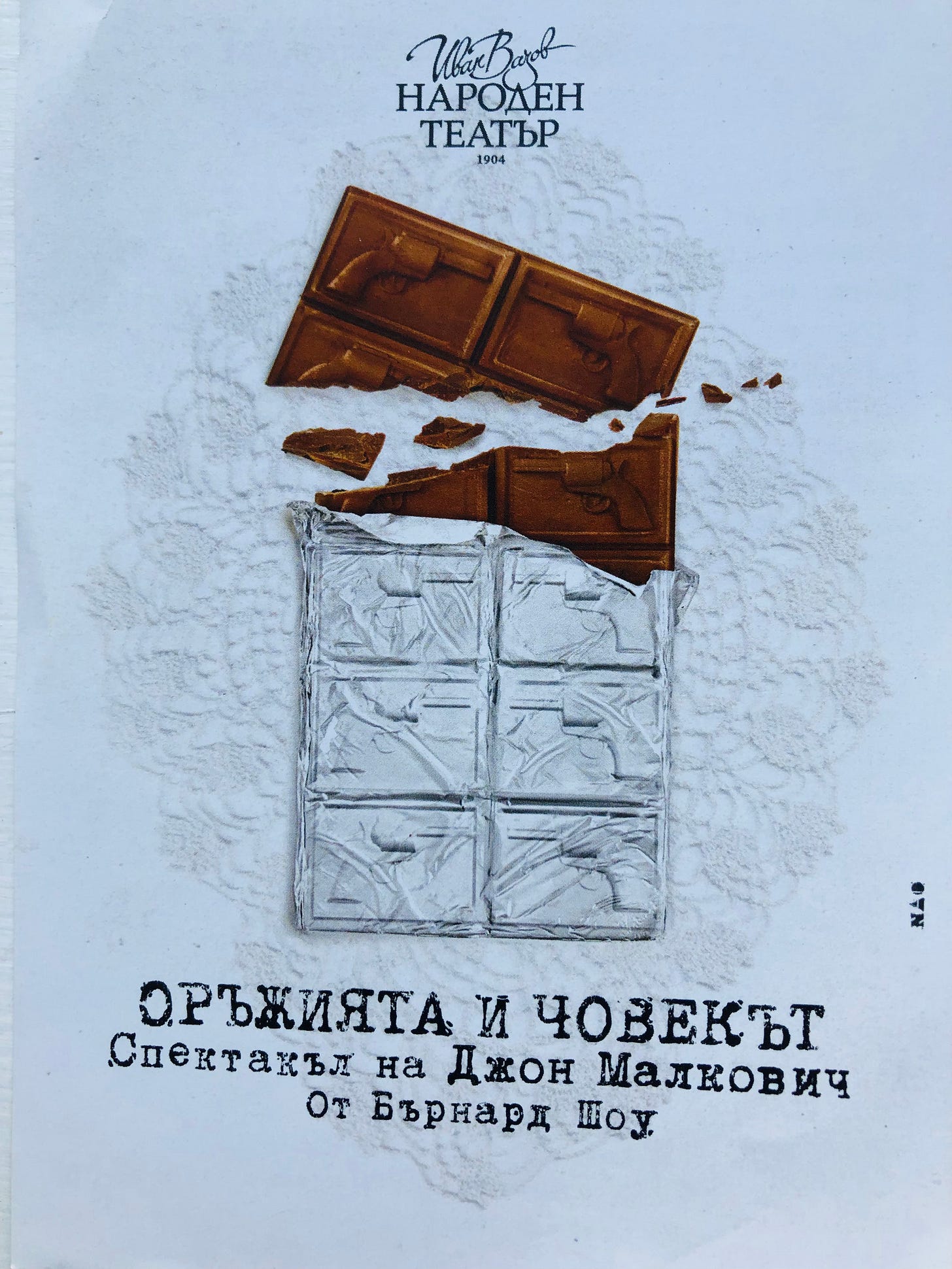

On my first day in Sofia, right after I left the clinically depressed tourist office worker, I found myself in front of the National Theatre, just across the square. I was considering the building’s architecture–a strange mix of the neoclassical and the garish–when my eyes fell on posters presumably advertising the performances.

It is a sad fact about me that in college I tried and painfully failed to learn Russian. At the time, I found it acutely embarrassing that I just could not grasp the concept of declension, and today, the only things I retain from those traumatic language lessons are the words for ‘I love you,’ and a remedial ability to decipher the Cyrillic alphabet. I was painstakingly sounding out the words on one of the posters when I realized they read “John Malkovich.”

And then I remembered: a couple of months earlier I had read something in the news about the protests that erupted around a John Malkovich-directed version of Shaw’s play Arms and the Man when it opened…in Sofia.

When he was asked to direct something for the Bulgarian National Theatre, the American Malkovich chose Arms and the Man because it is set in Bulgaria. Shaw, who was Irish, had written the play as a comedy that takes place during the 1885 Serbo-Bulgarian war to critique the romanticization of both love and armed conflict. It’s fair to say that neither Shaw nor Malkovich imagined that the mere staging of the work would result in angry, even violent, protests from Bulgarian nationalists upset with how the Bulgarians in the play are depicted. But that’s exactly what happened when the Malkovich-directed version debuted in November 2024 to a near empty playhouse, much of the audience having been intimidated or physically blocked from entering from demonstrators outside.

There were a few more police on hand than strictly necessary by the time I saw the play a few months later. But there were no protestors, and inside, the jewelbox theater was packed. The performance was subtitled in English, so I could actually understand what turned out to be a bedroom farce that, via observant servants and a clear-eyed mercenary soldier, pokes fun at the aristocracy and one particularly pompous war hero, for the stories they tell themselves about love, war, and class. Throughout, the audience roared with laughter, and they gave it a standing ovation at the end. (Malkovich, alas, was nowhere to be seen.)

In the lobby after, I talked with Anna and Lubo. Both in their mid-20s, they didn’t like the play, but they also didn’t like the people who had protested it. Come to think of it, they weren’t big fans of the audience either.

“This will be controversial, but I didn’t think it was so great,” Anna said. “The play wasn’t nearly as funny as the audience was making it out to be.”

Recently returned from studying in Glasgow, neither was exactly impressed with the relative sophistication of their compatriots. But they also didn’t like the way the play depicted Bulgarians.

“ It misrepresents us, it exaggerates how in love we are with war and fantasy,” Lubo said.

“Isn’t that what the protestors were saying?” I asked.

“The protests were outrageous,” Anna interrupted. “Yes, they were upset because they thought it misrepresented Bulgarians. But to be so offended that you act like a barbarian and push people around outside the theater? It’s disgusting.”

They were also disturbed because in the Venn diagram of present-day Bulgarian nationalists protesting a 19th-century Irish play and present-day Bulgarian supporters of Putin, there is significant overlap. “Our parents and grandparents think things were better under Russia, but there are also a lot of young people who like Putin and think Bulgaria will be stronger if we are closer to Russia,” Anna said. “They don’t understand the levels of disinformation they are being fed, or that there are still so many Russian spies here.”

They both conceded that Shaw had gotten some elements of Bulgarian character right, like its concern with class and social status. “Bulgarians think that if you are up here,’’--here Anna raised her hand to eye level– you are intelligent, beautiful and good. And if you are down here--she lowered it– “you are the opposite.”

The thing is, Shaw never intended to say anything at all about Bulgarians. I did some research on the play when I got home, and discovered he didn’t choose the setting until the script was almost done. It “was nearly finished before I had settled on its locality,” he explained right before the play premiered in London in 1894. Knowing that he wanted a war as backdrop but being, in his words, “absolutely ignorant of history and geography;” he went around asking his friends if they knew of any good conflicts going on. “At last Sidney Webb told me of the Serbo-Bulgarian war,” Shaw said. “So I looked up Bulgaria and Serbia in an atlas, made all of the characters’ [names] end in ‘off’, and the play was complete.”

Nearly 150 years later, that off-the-cuff decision in a work of fiction had given rise to a bit of low-level violence and intimidation in real life. Maybe that’s because, as I had discovered, the past seemed more present in Sofia than in most European capitals I’ve visited. Or maybe, in its indication of nationalist sensitivities, it is just one more sign of the present we are entering.

The Addresses

Below, you’ll find a list of the places where I ate, drank, and stayed in Sofia. But, a gentle reminder: wouldn’t it be more fun to find your own?